'What seemed missing in Tumbbad was that screwiness, that kinkiness, which shades so many of our best parables,' observes Sreehari Nair.

Rahi Anil Barve's Tumbbad isn't as much a horror film as it is a fairy tale for grown ups.

An old woman is lulled into sleep by a threat classically reserved for children: 'Sleep oh old lady, or the devil will be here!'

There are underlayers of starving monsters and webby secret chambers, but no Alices or compassionate barn spiders. The labyrinths in the film open exclusively for brutes and testosterone-drenched men.

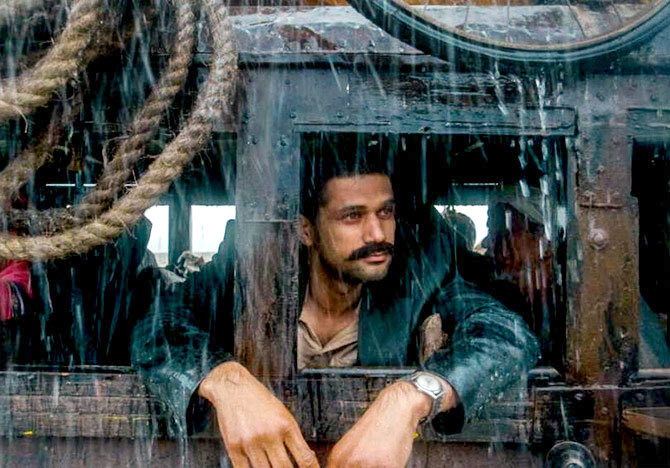

Chief among these brutes is Vinayak Rao (Sohum Shah), a monomaniacal gold-seeker in the Maharashtra of early 1900s.

Rao is like Aguirre from Herzog's The Wrath of God; only, it's a one-man army that he commands.

Like Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood,(Sohum Shah's face, moustache, and untrusting eyes are styled to resemble that of Plainview's), Vinayak Rao believes that the secrets of the earth and for the 'men of the earth' to uncover.

As a boy, Rao cracks the code to his ancestral gold at the precise instant that he loses his younger brother: He is too charged by the vision of treasure and far-off adventure to mourn his brother's death. Rao is a brother who acts unbrotherly, and later, as a father, someone who does unfatherly things.

The story, one part of a mythology, talks about how greed is an inescapable cycle, a matter of inheritance passed down from fathers to sons -- seen this way, the film is a critique of capitalism.

There's a powerful parable at work here, but what Tumbbad fails to do is use the medium of cinema to convey the power of that parable.

While the arc of Vinayak Rao's life resembles an epic, what we don't feel is the emotional rush of epic storytelling.

The sense of dread is steady, but it's not a lyric sense of dread.

The images of nature, what with the Rashomon-like rain, attempt to overpower you, but they don't have that sensuous pull.

Movies affect our senses so directly because they can retain their honesty even when they turn corrupt. (Cinema must be our only hope for great tawdry art).

In Tumbbad, our apprehensions are raised lazily and we wait like masochists for the manipulations to arrive, but what we get instead is a single-line moral.

Barve and his co-writer (Anand Gandhi of The Ship of Theseus fame) have evidently proceeded from a big chunk of material -- a lot of which is safe-kept in their heads. But because the manifestations of that safe-kept material are not present clearly in the narrative, we are never quite invited in.

The parable looms over everything; so much so that even the layered gags feel untapped.

Vinayak Rao's quest for gold begins with him as a boy covered in wheat flour and it culminates in his using the flour as a bait to tame the otherworldly creature that guards his ancestral treasure.

This goes on and we see the wheat flour becoming an inextricable part of Rao's domestic life but the gag doesn't stand out in a way that it should have for us to feel like a part of what is going on.

The dialogues play for economy but sound stunted (Why, oh, why wasn't this film made in Marathi?).

The undercurrent of incessant moralising (there are no speeches thankfully, but the moralising tone flows relentlessly as it did in The Ship of Theseus) does not allow for the scenes to be shaped. And so, even when the story hops about 1918, 1933 and 1947, the effect is static.

As I looked back at the film, what seemed missing in Tumbbad was that screwiness, that kinkiness, which shades so many of our best parables.

Why we love the tale of Scheherazade in 1001 Nights is because at its core is a bloodthirsty monarch whose first reaction to boredom is killing.

There's just that tinge of insanity given its due, which raises the storytelling risks.

Why we prefer the Panchatantra to Aesop's Fables is because the former is more amoral and screwy and gleefully so (The War of Crows and Owls is deliciously savage, but how well we get its message).

In untying its parable about greed, Tumbbad keeps its shadings at a safe distance -- and so the parable at its centre does not extend its bounds; it feels not bracing enough. (We are never swimming in it, only playing distant observers).

Vinayak Rao has a mistress (Ronjini Chakraborty), who is his reward for his wealth and his power, and when Rao's little son after his first treasure-digging expedition stakes his claim over this mistress, the underlying drama there has all the makings of a great sick joke.

But Barve and his writers treat it merely as a sign of decadence.

This means that the scene does not become tragicomic -- which was its true potential.

For the fantasy in Tumbbad to work, the reality had to seem equally frightening and crazy; but because the realities surrounding the parable are trimmed away before their emotional peaks are hit, the scares never quite reach us.

And when the fantasy finally kicks in, secret chambers are opened to variations of the same secret. There is no density of imagination; the aura is that of a one-trick children's fable.

A combination of beauty and horror is the device that best communicates to us terrible truths -- this, we don't get in Tumbbad.

The look of the film is Goya meets Graphic Novel; with scenes shot either in the claustrophobic darkness of Puneri Wadas or colour-drained outdoors. (In this sense, the self-serious tone feels well spread out).

I was yearning for some fireworks of moviemaking to compensate for the cold allegory. But what you get at the most is the camera used as a constant companion to the actors: Following them tightly or held smack-up against their anxious faces.

The reliefs in Tumbbad are delivered through whatever little touches seep out of its outsized source material.

When Vinayak Rao's wife opens her own flour mill, the message on the board outside reads: 'Get your cereals ground by a Brahmin Lady!'

The board outside Vinayak Rao's friend's house reads, 'You only have to knock thrice; we are not deaf.'

A trip to Pune will tell you that such messages hold a mirror to the city's distant attitude (Shops in Pune still have boards with requests of order of: 'Please do not ask us for directions!!!')

Vinayak Rao's relationship with his son is the most interesting dynamic in the film.

In an awfully moving stretch of the story, the kid is shown to be getting physically ready to accompany his father on his treasure-digging trip. But Rao knows that it's not about physical readiness: He senses that the boy isn't greedy enough; that he takes after his mother and not him.

By the time we get to this last act of his life, Vinayak Rao is a lonely, distrustful man whose success is shown to spawn even more paranoia.

I occasionally got the feeling that perhaps the movie needed a grander lead (someone who could tower over the landscape and then slowly shrink down) but Sohum Shah does very well.

He brings in the Marathi inflections smartly, and it is majorly owing to his intuitions as an actor that his character isn't turned into an outright animal.

The parable of Tumbbad is out to de-humanise Vinayak Rao, but Sohum Shah preserves his humanity.

The film is straight Church Work. But Shah keeps even his curses close to prayers.