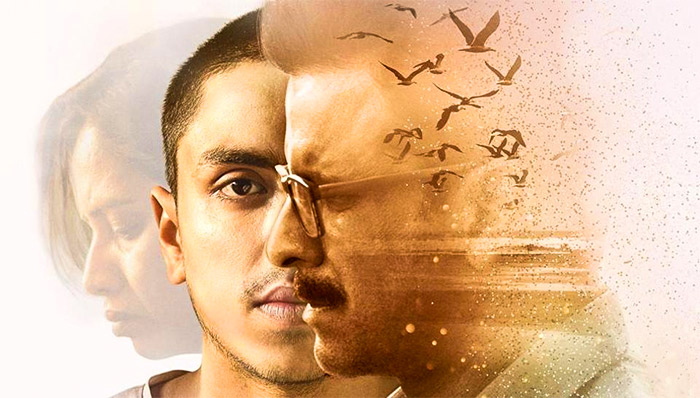

Rukh may be lit like a YouTube Short Film and may have its share of other technical problems, but there’s something disturbingly original about director Atanu Mukherjee’s vision, feels Sreehari Nair.

If it was Joan Didion who said, 'We tell ourselves stories in order to live,' Atanu Mukherjee’s Rukh is about the stories we hide from one another in order to continue living.

The protagonist of the movie, Dhruv (Adarsh Gourav), is a Boy-Hamlet who becomes obsessed with solving the mystery of his father’s (Divakar, played by Manoj Bajpayee) death in a car accident. Dhruv smells foulness about the blood spilled, but to convince those around him about his intuition, he has to first break their stony silences.

The people in Rukh all talk and behave like the soul-dead characters in an Antonioni film.

However, Mukherjee and his writers are clear about not turning this into a superficial story about the failure to communicate; on the contrary, it’s about retreating to ‘incommunicado’ as the only viable line of defense.

On a very primal level, this is a film about parents trying to shield their children from life’s painful truths, smoothing out their ‘toughies’ with a ribbon or two of pep-talk and realising for themselves that those pep-talks amount to dross in the face of life’s many insolubles.

It is about growing up, and about how difficult it is to be a grown-up. This is a motion picture that peddles coming-of-age and, at the same time, shows us its absurdities.

Atanu Mukherjee’s directorial approach lacks the formal polish of trained hands: the scenes are framed without much imagination, the lighting seems straight out of those YouTube Short Films, and the dialogues by Vasan Bala -- kept consciously humdrum and pointing to the mundane -- have not been shaped right (even with their starkness, the lines just don’t sound like daily-speak).

Plus, there’s the oppressive tendency to lop off scenes at an exact point of revelation. And I have to tell you, I find this narrative choice seriously soap-operaish -- for it demolishes the natural architecture of the scenes and had bugged me to no end when applied in such faux-suspenseful movies as Kahaani, Talaash, TE3N and Wazir.

The idea, I get it, is to pump up the tension, but all that this technique achieves is make you recall the old narrative-wisdom: in the race for tension, it is the hacks who ‘withhold information’; the masters simply give it to you.

The lack of cinematic exuberance in Rukh irks but it also becomes a curious fit for one of the movie’s subsidiary subjects: the sweating off of capitalism’s glamours, the idea of money as a suicide note, a cause for decay so strong that it’s shown here to kill smiles and tear relationships apart.

Mukherjee’s rich all live in a world of constant dread, develop precarious habits and even get manipulated by the poor (A big real-estate developer wears a nervous smile throughout and, after a long-awaited night of relief and partying, gets cornered by a traffic cop who lectures him about road decorum after accepting from him a big wad of cash).

The chief antagonist of the movie is the Faustian character, Robin, who bankrolls Divakar’s leather business using illegal capital, deserts him at a critical juncture and then tries to use Divakar’s death as an opportunity to save his ass.

Robin would have been rank despicable, except that he is played here by Kumud Mishra whose intelligence as an actor turns the character into a graceless despot.

Mishra’s Robin is forever gambling on the edge of despair; you can catch his bluff but he keeps trying nonetheless.

In a brilliantly-acted scene, Robin tries to convince Divakar’s accountant to vouch for him at a CBI investigation and he breaks away from his pleading to compliment the accountant on his daughter -- 'Bachi badi ho gayi hai,' he remarks with an ambiguous smile. (There he is trying to bring in the whole history of their association into his appeal and he’s so bad at it that you feel for him. God, this Kumud Mishra can complicate your responses!)

If Robin is the opportunist who has no opinions, only reflexes and scattered irritations, there’s Manoj Bajpayee’s Divakar who can be termed a ‘bad businessman’ for the simple reason that he feels for those around him.

When the CBI rounds him up for financial irregularities, Bajpayee’s upper lip trembles a little and, starting from that scene, you see his Divakar shrinking with every passing appearance till, finally, he’s just a body covered in a white sheet with only a name-tag for identity.

The story of Divakar and Robin, a story of an uncomfortable friendship that transmutes into open enmity, is the movie’s basic thrust and we discover this arc through Dhruv’s eyes -- sharing his titillations, partaking in his misjudgments and growing as oblique as he does. And, by the end, Dhruv's investigations, and his tendency to go too far, become a reflection of the misplaced pride of men like Divakar and Robin.

Rukh may not be a film about the follies of men, but it is nevertheless about men who commit follies, who look away from their women when their vanities are destroyed, who walk away from the scene like fallen stars and finally fade out.

And living through the Gothic premonitions that such actions of their men generate, the women and their silent deliberations emerge as the movie’s strongest voices.

Thirty-four-year-old Smita Tambe as Nandini, playing mother to 18-year-old Dhruv and wife to Divakar, has a face that suggests the death of a long-cherished dream.

As the movie progresses, and as Divakar’s frame slowly crumbles, she withdraws into her maiden name and then into her mother’s home, where, in the tradition of those steely women, she tries to rebuild the nest for Dhruv.

I started this review with a mention of Joan Didion because there’s a sense of unremitting anxiety in Rukh that reminded me of her writing. And you can figure out that perhaps this kind of anxiety is Atanu Mukherjee’s driving sensibility as well.Â

The ending of the movie however suggests that Dhruv has grown into a better, almost ‘simpler’ person. In a clear veering from the movie’s part-crummy but felt tone, it then becomes a throwback to all those educated cliches we’ve heard and gotten bored of: of letting go, wind chime being put up and the slo-mo walk of maturity.Â

Adarsh Gourav’s face, at the moment that he registers a dark truth, has a scorching immediacy to which we can connect with readily. When he mellows down though, that face turns into an advertising platitude.

The movie seems to advocate that it’s Dhruv’s maturity that rescues him from the pits of hell. However, in an early scene, which has Divakar and Robin getting into a fight, it’s Divakar who represents the paradigm of ‘the grown-up,’ but that doesn’t necessarily save him.

The ending of the movie is split and it is a suck-up, because Atanu Mukherjee pulls back from what he had been digging out.Â

Like Divakar’s final duel, in which he forsakes the coins on the board and keeps his chess-loving father suspended in limbo, Mukherjee, after establishing his unique voice, leaves the game unfinished. Â

Â