Kabali has nothing new to say or offer, besides Rajinikanth playing his age, feels Raja Sen.

Kabali has nothing new to say or offer, besides Rajinikanth playing his age, feels Raja Sen.

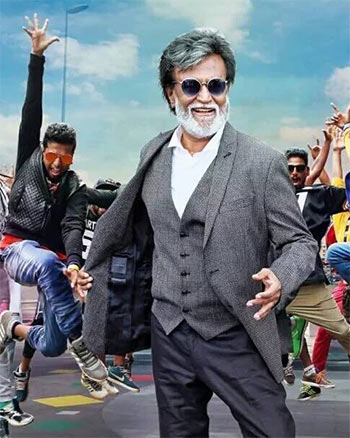

Nearly halfway into the new Rajinikanth release, Kabali, a student mockingly asks Rajinikanth’s character, Kabali, about the need to be constantly clad in fancy suits and sunglasses.

It is a pertinent question even from the perspective of the audience, because while the superstar actor might (mostly) have forsaken the dark-haired wigs, his character is still dressed with eye-catching distinctiveness.

Kabali laughs, for it is a query he has faced often, throughout his rise from an impassioned young activist partial to garish silken shirts, to a revered gangster with an eye for well-tailored waistcoats.Â

The reason he gives for his sartorial excess -- several times through the film, as the question continues to dog him -- is that he wears clothes like the rich man in order to emphasise how someone like him, not born to wealth or greatness, is equal to the rich man.

Set in Malaysia, Kabali tells the story of the large but marginalised Tamil community there, and how the Tamilians are not considered equal to the locals or the Chinese. When a guy from his gang asks him if he’ll spend all his money on suits, Kabali smiles and suggests the guy start dressing sharper too.

It’s all about impact, he states, explaining that there was a reason Babasaheb Ambedkar always wore a suit and Mahatma Gandhi never did.Â

This is a wonderful way to rationalise the Grandmaster Flash aspect of the Rajinikanth mystique.

Director Pa Ranjith, however, has more racial ammunition in hand.

When asked what his lovely wife saw in him, Rajini emphasises the darkness of his skin, using it as a metaphor for intensity, power and virility.

"Black power," he says, before Radhika Apte, who plays his wife in the film, looks at him and expresses her desire for his darkness to be rubbed against her. In a film about a downtrodden community looking to prove itself, this attention to the colour of the superstar’s skin is not coincidental.

Despite the political sincerity, however, this film nothing new to say or offer, besides Rajinikanth playing his age.

This leads to many a great moment as Rajini inevitably slides into Amitabh Bachchan mode and chews on his lines before spitting them out with speeding-bullet force. We haven’t seen him like this before, grey and brooding and with his dynamism coiled up on the inside, and the result is quite stunning simply because of that incredible screen presence he commands -- and the fact that he is who he is.

The idea that Rajinikanth, 65, could kick each of our posteriors, is a relatively easy one to buy, and this film capitalises on the fact that we don’t quite question it.

True, the fight scenes often consist of villains politely waiting their turn so he can take his time to attack them, but when he does attack, he does so with gusto.Â

The rest is humdrum.

Regardless of the Bali Brahmbhatt clones in Michael Jackson clothes who sing of Kabali’s legend, it seems cobbled from many a source, most recognisably The Godfather but also, oddly and gender-agnostically, from Kill Bill.

Kabali has gone to prison for 25 years following a massacre at a mandir, and he’s back gunning for revenge. But he's also trying to help troubled youths get a better life.

The villain is a man called Tony Lee, who works for someone named Ang Lee. It is thus rather cute that Tony Lee -- always referred to by his full name, perhaps to symmetrically pit Ka-ba-lee versus To-ny-lee -- is played by Winston Chao, who once starred in Ang Lee’s beautiful Eat Drink Man Woman.Â

Tragically, however, Chao -- who struggles with villainous English -- never quite gets the hang of things here and comes across as rather comical, as does this film’s entire third act.

The drama is all there but as the bodies pile up, so do the laughs, and the whole thing comes together rather cartoonishly.

All the actors seem to be performing in a different pitch, and -- besides Rajinikanth enjoying this rare modern-day performance of relative restraint -- everyone else is all over the place. At one point in the film, Apte hyperventilates with such enthusiasm I was convinced her character had been rendered mute.Â

What is interesting, besides Rajinikanth, is the wonderfully mixed iconography Pa Ranjith throws together in this film about immigrants and borrowed cultures.

Celtic tattoos vanish into formal shirt collars, samurai swords are laid upon corpses wreathed in garlands, an Ambedkar portrait is hung up next to that of Che Guevara, a character’s stupidity is emphasised by a Being Human shirt... These are all details that give the film both authenticity and surreality in equal measure, and they make me strongly suspect that this could have been a far more gripping and finessed film without Rajinikanth in it -- and without, thus, all sorts of alterations due to worried producers and commercial considerations.

But then would we be talking about it at all?

Rediff Rating:Â