For all its do-gooder fixation, Phullu neither has the passion to succeed as a film nor the seriousness of a valuable message, feels Sukanya Verma.

Well-meaning films do not always translate into well-made films.

Director Abhishek Saxena wishes to address the issue of the menstrual taboo and spread awareness regarding hygiene among the rural women of India.

But his feeble incentives and simplistic endeavours don't quite add up or allow Phullu to become the heartfelt wake-up call it so desperately wants to be.

Set in a village that receives low voltage electricity for only one hour in a day, Phullu paints an authentic milieu yet spends too much time focusing on the carefree ardour of its titular protagonist.

In this over eagerness to both entertain and educate, Saxena somewhere bungles up on the ratio. The upshot is sloppy and unconvincing.

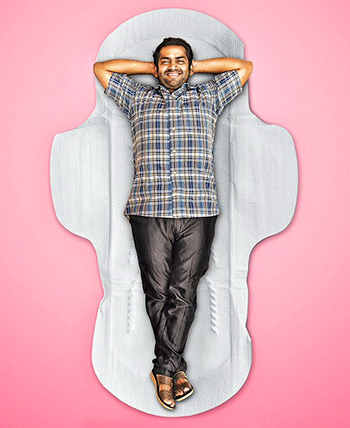

A clueless, curious bum (Sharib Hashmi) with a grand vision doubles up as a courier of sanitary napkins aka saaman for women who cannot make a trip to the city themselves.

It's not his real job. He doesn't have any. He doesn't want any.

All he wants to do is reduce every woman's pain, something that's reduced to crude innuendo in this film.

But it baffling how for all the compassion Phullu displays towards the opposite sex, he has zero concern for his toiling, understandably furious old mother.

Even marriage makes no difference to his loafing. That the women in his life are played with remarkable gusto by Nutan Surya and Jyoti Sethi deflect some of the attention away from this.

Even so, a good chunk of this 96-minute rambling drama is whiled away in the romance of newly weds against frequently popping songs.

By the time Phullu feels a compulsive need to fix the way periods are treated in his part of the world, he's coming across as too much of a dunce and drifter to be taken seriously.

- Should there be an emoji about periods?

Saxena never persuasively explains what prompts Phullu's sympathy for a cause he doesn't even understand.

Nor is the narrative bothered with the practicality of his bizarre experiments to produce cost effective sanitary pads, as it races towards its ambiguous conclusion.

Hashmi is earnest, but the writing is all over the place. His naiveté is overstressed to the point that his actions look farcical.

No wonder a brief cameo by Inaamulhaq, once again reiterating his appeal in showy, idiosyncratic characters, makes more sense that most of this movie.

What would at most be acceptable as a short film issued in the public interest is stretched to bizarre lengths.

Phullu unwisely presumes that promoting a humanitarian angle absolves it of mediocrity.

For all its do-gooder fixation, Phullu neither has the passion to succeed as a film nor the seriousness of a valuable message.