'Philosophy, politics and practicality cross paths in Mohalla Assi's ambitious premise.'

'Except it is directed in such an unwieldy fashion that instead of rich satire, what emerges is a lumbering flab of incoherence and opinion glut,' notes Sukanya Verma.

An ancient city, both proud of and burdened by its heritage steeped in religion and spirituality, culture and casteism -- Varanasi, Benares or Kashi -- is far too complex and conflicting to explain in a few words.

In Dr Kashi Nath Singh's Kashi Ka Assi, a novel spanning various decades and countless discussions, a good deal of time is devoted in observing the shifting mood and mind-set of residents of Assi, a prominent neighbourhood on the ghats of Kashi. What lends it distinction is the everyday politics and expletives-laden language.

The colourful character and cynicism of their provocative dialogue and the dilemma it carries is somewhat lost in Dr Chandraprakash Dwivedi's rambling, rabble-rousing adaptation for the big screen.

A dated air envelops Mohalla Assi's film-making, which chronicles the changes transpiring at the end of the 1980s, heading towards the new millennium, especially when its characters speak for effect, and are aware of its audience.

Strewn with protagonists shaped by their unique prejudices and principles, it labours to isolate Varanasi's hallowed identity and devout atmosphere. By the banks of the holy Ganga, an entire community engages in the business of prayer and dharma.

There are pandits chanting scriptures, conducting rituals, supervising ceremonies or teaching Sanskrit in the tradition of their staunch Brahmin ancestors.

There are retired professionals and flag bearers of Hindutva defending and discussing the city's politics and slow demise over bhaang and chai at a regular haunt -- a thinking man's adda.

A smarmy tourist guide speaks glibly of the land of mistakes.

He means mystiques.

'It's all the same,' he insists before rattling off some more paradoxes and marketing its magnetism to foolishly grinning foreigners seeking culture and cannabis in equal measure.

A little farther off the ghats, a pair of housewives share their woes and worries while going about their daily chores revealing a connection to society behind closed doors.

If one's husband and his complete lack of scruples is proving advantageous, another's bigotry and refusal to adapt around an evolving socio-economic structure is leading to penury.

Their domestic ups and downs alternate as the central and peripheral arc overlapping several others.

Philosophy, politics and practicality cross paths in Mohalla Assi's ambitious premise. Except it is directed in such an unwieldy fashion that instead of rich satire, what emerges is a lumbering flab of incoherence and opinion glut.

Dwivedi stuffs in abundant history and point of view.

Despite the credibility of its information or plainness of its bias, the action unfolds much too haphazardly to truly appreciate.

Between Mohalla Assi's commitment to the politics of religious ideology, rampant globalisation, fraudulent god men, fumbling governments and the impact of a poor pandit's stubborn social stand on his family and the struggling panda community, the experience is awfully cumbersome.

Assi's trademark profanity occupies every sentence of the movie.

But if it sounds more contrived than crude, blame it on the actors and how consciously they deliver them. There's simply no sur to their swearing.

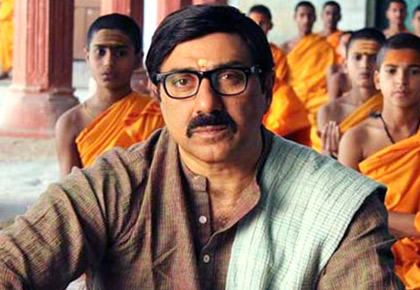

Sunny Deol is terribly miscast as the stuck-up pandit spearheading a kar sevak rally, resisting foreigner lodgers and moaning about the declining demand for Sanskrit teachers.

More parrot than priest, he appears to be reading out his lines from a teleprompter.

Amidst Mohalla Assi's space of stagey, inconsistent performances, Sakshi Tanwar brings out the insecurities and irritation of her confined authority with spark and sass.

Dwivedi's knowledge of language, clarity of thought and profound understanding of India's value system has defined his creativity.

It is most striking only when the film takes a break from its endless yak yak to question and not answer.

Is Varanasi dying, evolving or compromising?

Do its denizens offer allegiance to faith or seek freedom from it?

Is God's omnipresence a matter of relief or argument?

Is Mohalla Assi worth the trouble?